Properties of the carbon atom:

| 200 | Properties of the atom | |

| 201 | Atomic mass ( molar mass )* | 12.0096-12.0116 amu (g/mol) |

| 202 | Electronic configuration | 1s2 2s2 2p2 |

| 203 | Electronic shell | K2 L4 M0 N0 O0 P0 Q0 R0 |

| 204 | Atomic radius (calculated) | 67 pm |

| 205 | Empirical atomic radius | 70 pm |

| 206 | Covalent radius* | 76 pm |

| 207 | Ion radius (crystalline) | C4+ 29 (4) pm, 30 (6) pm (in parentheses the coordination number is indicated - a characteristic that determines the number of nearest particles (ions or atoms) in a molecule or crystal) |

| 208 | Van der Waals radius | 170 pm |

| 209 | Electrons, Protons, Neutrons | 6 electrons, 6 protons, 6 neutrons |

| 210 | Family (block) | p-family element |

| 211 | Period in the periodic table | 2 |

| 212 | Group on the periodic table | 14th group (according to the old classification - the main subgroup of the 4th group) |

| 213 | Emission spectrum |

Application

Graphite is used in the pencil industry. It is also used as a lubricant at particularly high or low temperatures.

Diamond, due to its exceptional hardness, is an indispensable abrasive material. The grinding attachments of drills are coated with diamond. In addition, cut diamonds are used as gemstones in jewelry. Due to its rarity, high decorative qualities and a combination of historical circumstances, a diamond is invariably the most expensive gemstone. The exceptionally high thermal conductivity of diamond (up to 2000 W/m•K) makes it a promising material for semiconductor technology as substrates for processors. But the relatively high price (about $50/gram) and the difficulty of diamond processing limit its use in this area. In pharmacology and medicine, various carbon compounds are widely used - derivatives of carbonic acid and carboxylic acids, various heterocycles, polymers and other compounds. Thus, carbolene (activated carbon) is used to absorb and remove various toxins from the body; graphite (in the form of ointments) - for the treatment of skin diseases; radioactive carbon isotopes—for scientific research (radiocarbon dating).

Carbon plays a huge role in human life. Its applications are as varied as this many-sided element itself.

Carbon is the basis of all organic substances. Any living organism consists largely of carbon. Carbon is the basis of life. The source of carbon for living organisms is usually CO2 from the atmosphere or water. Through photosynthesis, it enters biological food chains in which living things devour each other or each other's remains and thereby obtain carbon to build their own bodies. The biological cycle of carbon ends either by oxidation and return to the atmosphere, or by burial in the form of coal or oil.

Carbon in the form of fossil fuels: coal and hydrocarbons (oil, natural gas) is one of the most important sources of energy for humanity.

Chemical properties of carbon:

| 300 | Chemical properties | |

| 301 | Oxidation states | -4 , -3 , -2 , -1 , 0 , +1, +2, +3, +4 |

| 302 | Valence | II, IV |

| 303 | Electronegativity | 2.55 (Pauling scale) |

| 304 | Ionization energy (first electron) | 1086.45 kJ/mol (11.2602880(11) eV) |

| 305 | Electrode potential | |

| 306 | Electron affinity energy of an atom | 121.7763(1) kJ/mol (1.2621226(11) eV) – 12C carbon, 121.7755(2) kJ/mol (1.2621136(12) eV) – 13C carbon |

Being in nature

The carbon content in the earth's crust is 0.1% by mass. Free carbon is found in nature in the form of diamond and graphite. The bulk of carbon is in the form of natural carbonates (limestones and dolomites), fossil fuels - anthracite (94-97% C), brown coal (64-80% C), bituminous coal (76-95% C), oil shale (56- 78% C), oil (82-87% C), flammable natural gases (up to 99% methane), peat (53-56% C), as well as bitumen, etc. In the atmosphere and hydrosphere it is found in the form of carbon dioxide CO2, in the air there is 0.046% CO2 by mass, in the waters of rivers, seas and oceans it is ~60 times more. Carbon is included in the composition of plants and animals (~18%). The human body enters carbon through food (normally about 300 g per day). The total carbon content in the human body reaches about 21% (15 kg per 70 kg body weight). Carbon makes up 2/3 of muscle mass and 1/3 of bone mass. Excreted from the body mainly through exhaled air (carbon dioxide) and urine (urea). The carbon cycle in nature includes the biological cycle, the release of CO2 into the atmosphere during the combustion of fossil fuels, from volcanic gases, hot mineral springs, from the surface layers of ocean waters, etc. Biological The cycle is that carbon in the form of CO2 is absorbed from the troposphere by plants. Then from the biosphere it returns again to the geosphere: with plants, carbon enters the body of animals and humans, and then, when animal and plant materials rot, into the soil and in the form of CO2 into the atmosphere.

In a vapor state and in the form of compounds with nitrogen and hydrogen, carbon is found in the atmosphere of the Sun, planets, and is found in stone and iron meteorites.

Most carbon compounds, and above all hydrocarbons, have a pronounced character of covalent compounds. The strength of simple, double and triple bonds of C atoms with each other, the ability to form stable chains and cycles from C atoms determine the existence of a huge number of carbon-containing compounds studied in organic chemistry.

Physical properties of carbon:

| 400 | Physical properties | |

| 401 | Density* | 1.8-2.1 g/cm3 (at 20 °C and other standard conditions, state of matter – solid) – amorphous carbon, 2.267 g/cm3 (at 20 °C and other standard conditions, state of matter – solid) – graphite, 3.515 g/cm3 (at 20 °C and other standard conditions, state of matter – solid) – diamond |

| 402 | Melting temperature | |

| 403 | Boiling temperature | |

| 404 | Sublimation temperature | 3642 °C (3915 K, 6588 °F) – graphite |

| 405 | Decomposition temperature | 1000 °C (1273 K, 1832 °F) – diamond. Diamond decomposition products – graphite |

| 406 | Self-ignition temperature of a gas-air mixture | |

| 407 | Specific heat of fusion (enthalpy of fusion ΔHpl) | |

| 408 | Specific heat of evaporation (enthalpy of boiling ΔHboiling) | 715 kJ/mol (sublimation) |

| 409 | Specific heat capacity at constant pressure | |

| 410 | Molar heat capacity* | 8.517 J/(K mol) – graphite, 6.155 J/(K mol) – diamond |

| 411 | Molar volume | 5.314469 cm³/mol – graphite, 3.42 cm³/mol – diamond |

| 412 | Thermal conductivity | 119-165 W/(mK) (under standard conditions) – graphite, 900-2300 W/(mK) (under standard conditions) – diamond |

| 413 | Thermal expansion coefficient | 0.8 µm/(MK) (at 25 °C) – diamond |

| 414 | Thermal diffusivity coefficient | |

| 415 | Critical temperature | |

| 416 | Critical pressure | |

| 417 | Critical Density | |

| 418 | Triple point | 4326.85 °C (4600 K, 7820.33 °F), 10.8 MPa |

| 419 | Vapor pressure (mmHg) | 0.000000001 mmHg (at 1591 °C) - graphite, 0.00000001 mmHg. (at 1690 °C) - graphite, 0.0000001 mmHg. (at 1800 °C) - graphite, 0.000001 mmHg. (at 1922 °C) - graphite, 0.00001 mmHg. (at 2160 °C) - graphite, 0.0001 mmHg. (at 2217 °C) - graphite, 0.001 mmHg. (at 2396 °C) - graphite, 0.01 mmHg. (at 2543 °C) - graphite, 0.1 mmHg. (at 2845 °C) - graphite, 1 mmHg. (at 3214 °C) - graphite, 10 mmHg. (at 3496 °C) - graphite, 100 mmHg. (at 4373 °C) - graphite |

| 420 | Vapor pressure (Pa) | |

| 421 | Standard enthalpy of formation ΔH | 0 kJ/mol (at 298 K, for the state of matter - solid) - graphite, 717 kJ/mol (at 298 K, for the state of matter – gas) – graphite, 1.828 kJ/mol (at 298 K, for the state of matter - solid) - diamond |

| 422 | Standard Gibbs energy of formation ΔG | 0 kJ/mol (at 298 K, for the state of matter - solid) - graphite, 2.833 kJ/mol (at 298 K, for the state of matter - solid) - diamond |

| 423 | Standard entropy of matter S | 5.74 J/(mol K) (at 298 K, for the state of matter - solid) - graphite, 158 J/(mol K) (at 298 K, for the state of matter – gas) – graphite, 2.368 J/(mol K) (at 298 K, for the state of matter - solid) - diamond |

| 424 | Standard molar heat capacity Cp | 8.54 J/(mol K) (at 298 K, for the state of matter - solid) - graphite, 20.8 J/(mol K) (at 298 K, for the state of matter – gas) – graphite, 6.117 J/(mol K) (at 298 K, for the state of matter - solid) - diamond |

| 425 | Enthalpy of dissociation ΔHdiss | |

| 426 | The dielectric constant | |

| 427 | Magnetic type | Diamagnetic material |

| 428 | Curie point | |

| 429 | Volume magnetic susceptibility | -1.4·10-5 – graphite |

| 430 | Specific magnetic susceptibility | -6.2·10-9 – graphite |

| 431 | Molar magnetic susceptibility | -5.9·10-6 cm3/mol (at 298 K) – graphite, -6.0·10-6 cm3/mol (at 298 K) – diamond |

| 432 | Electric type | Conductor – graphite, dielectric – diamond |

| 433 | Electrical conductivity in the solid phase | 0.1·106 S/m – graphite |

| 434 | Electrical resistivity | 7.837 µOhm M (at 20 °C) – graphite |

| 435 | Superconductivity at temperature | |

| 436 | Critical magnetic field of superconductivity destruction | |

| 437 | Prohibited area | 5.46-6.4 eV (at 300 K) – diamond, 5.4 eV (at 0 K) – diamond |

| 438 | Charge carrier concentration | |

| 439 | Mohs hardness | 1-2 – graphite, 10 – diamond |

| 440 | Brinell hardness | |

| 441 | Vickers hardness | |

| 442 | Sound speed | 17500 m/s (at 20°C, the state of the medium is crystals, axis L100) – diamond, 12800 m/s (at 20°C, the state of the medium is crystals, axis S100) – diamond, 18600 m/s (at 20° C, state of the medium - crystals, axis L111) - diamond, 11600 m/s (at 20°C, state of the medium - crystals, axis S110) - diamond |

| 443 | Surface tension | |

| 444 | Dynamic viscosity of gases and liquids | |

| 445 | Explosive concentrations of gas-air mixture, % volume | |

| 446 | Explosive concentrations of a mixture of gas and oxygen, % volume | |

| 446 | Ultimate tensile strength | |

| 447 | Yield strength | |

| 448 | Elongation limit | |

| 449 | Young's modulus | 1050 GPa - diamond |

| 450 | Shear modulus | 478 GPa – diamond |

| 451 | Bulk modulus of elasticity | 442 GPa – diamond |

| 452 | Poisson's ratio | 0.1 – diamond |

| 453 | Refractive index | 2.417 (under standard conditions for line D, the wavelength of which is approximately 0.5893 μ) – white diamond |

Thermal conductivity and thermal conductivity coefficient. What it is

So what is thermal conductivity? From a physics point of view, thermal conductivity

– this is the molecular transfer of heat between directly contacting bodies or particles of the same body with different temperatures, in which the energy of movement of structural particles (molecules, atoms, free electrons) is exchanged.

To put it simply, thermal conductivity

is the ability of a material to conduct heat. If there is a temperature difference inside the body, then thermal energy moves from the hotter part of the body to the colder part. Heat transfer occurs due to the transfer of energy when molecules of a substance collide. This happens until the temperature inside the body becomes the same. This process can occur in solid, liquid and gaseous substances.

In practice, for example in construction for the thermal insulation of buildings, another aspect of thermal conductivity is considered, associated with the transfer of thermal energy. Let's take an “abstract house” as an example. In the “abstract house” there is a heater that maintains a constant temperature inside the house, say, 25 ° C. The temperature outside is also constant, for example, 0 °C. It is quite clear that if you turn off the heater, then after a while the house will also be 0 °C. All the heat (thermal energy) will go through the walls to the street.

To maintain the temperature in the house at 25 ° C, the heater must be constantly running. The heater constantly creates heat, which constantly escapes through the walls to the street.

Coefficient of thermal conductivity

The amount of heat that passes through the walls (and according to science, the intensity of heat transfer due to thermal conductivity) depends on the temperature difference (in the house and outside), on the area of the walls and the thermal conductivity of the material from which these walls are made.

To quantify thermal conductivity, there is a coefficient of thermal conductivity of materials . This coefficient reflects the property of a substance to conduct thermal energy. The higher the thermal conductivity coefficient of a material, the better it conducts heat.

If we are going to insulate a house, then we need to choose materials with a small value of this coefficient. The smaller it is, the better. Nowadays, the most widely used materials for insulating buildings are mineral wool insulation and various foam plastics.

A new material with improved thermal insulation properties – Neopor – is gaining popularity.

The thermal conductivity coefficient of materials is designated by the letter ? (Greek small letter lambda) and is expressed in W/(m2*K). This means that if you take a brick wall with a thermal conductivity coefficient of 0.67 W/(m2*K), a thickness of 1 meter and an area of 1 m2.

, then with a temperature difference of 1 degree, 0.67 watts of thermal energy will pass through the wall. If the temperature difference is 10 degrees, then 6.7 watts will pass. And if, with such a temperature difference, the wall is made 10 cm, then the heat loss will already be 67 watts.

More details about the methodology for calculating heat loss in buildings can be found here.

It should be noted that the values of the thermal conductivity coefficient of materials are indicated for a material thickness of 1 meter. To determine the thermal conductivity of a material for any other thickness, the thermal conductivity coefficient must be divided by the desired thickness, expressed in meters.

In building codes and calculations the concept of “thermal resistance of a material” is often used. This is the reciprocal of thermal conductivity. If, for example, the thermal conductivity of foam plastic 10 cm thick is 0.37 W/(m2*K), then its thermal resistance will be equal to 1 / 0.37 W/(m2*K) = 2.7 (m2*K)/ Tue

Thermal conductivity coefficient of materials

The table below shows the values of the thermal conductivity coefficient for some materials used in construction.

| Material | Coeff. warm W/(m2*K) |

| Alabaster slabs | 0,470 |

| Aluminum | 230,0 |

| Asbestos (slate) | 0,350 |

| Fibrous asbestos | 0,150 |

| Asbestos cement | 1,760 |

| Asbestos cement slabs | 0,350 |

| Asphalt | 0,720 |

| Asphalt in floors | 0,800 |

| Bakelite | 0,230 |

| Concrete on crushed stone | 1,300 |

| Concrete on sand | 0,700 |

| Porous concrete | 1,400 |

| Solid concrete | 1,750 |

| Thermal insulating concrete | 0,180 |

| Bitumen | 0,470 |

| Paper | 0,140 |

| Light mineral wool | 0,045 |

| Heavy mineral wool | 0,055 |

| Cotton wool | 0,055 |

| Vermiculite sheets | 0,100 |

| Woolen felt | 0,045 |

| Construction gypsum | 0,350 |

| Alumina | 2,330 |

| Gravel (filler) | 0,930 |

| Granite, basalt | 3,500 |

| Soil 10% water | 1,750 |

| Soil 20% water | 2,100 |

| Sandy soil | 1,160 |

| The soil is dry | 0,400 |

| Compacted soil | 1,050 |

| Tar | 0,300 |

| Wood - boards | 0,150 |

| Wood – plywood | 0,150 |

| Hardwood | 0,200 |

| Chipboard | 0,200 |

| Duralumin | 160,0 |

| Reinforced concrete | 1,700 |

| Wood ash | 0,150 |

| Limestone | 1,700 |

| Lime-sand mortar | 0,870 |

| Iporka (foamed resin) | 0,038 |

| Stone | 1,400 |

| Multilayer construction cardboard | 0,130 |

| Foamed rubber | 0,030 |

| Natural rubber | 0,042 |

| Fluorinated rubber | 0,055 |

| Expanded clay concrete | 0,200 |

| Silica brick | 0,150 |

| Hollow brick | 0,440 |

| Silicate brick | 0,810 |

| Solid brick | 0,670 |

| Slag brick | 0,580 |

| Siliceous slabs | 0,070 |

| Brass | 110,0 |

| Ice 0°C | 2,210 |

| Ice -20°С | 2,440 |

| Linden, birch, maple, oak (15% humidity) | 0,150 |

| Copper | 380,0 |

| Mipora | 0,085 |

| Sawdust - backfill | 0,095 |

| Dry sawdust | 0,065 |

| PVC | 0,190 |

| Foam concrete | 0,300 |

| Polystyrene foam PS-1 | 0,037 |

| Polyfoam PS-4 | 0,040 |

| Polystyrene foam PVC-1 | 0,050 |

| Foam resopen FRP | 0,045 |

| Expanded polystyrene PS-B | 0,040 |

| Expanded polystyrene PS-BS | 0,040 |

| Polyurethane foam sheets | 0,035 |

| Polyurethane foam panels | 0,025 |

| Lightweight foam glass | 0,060 |

| Heavy foam glass | 0,080 |

| Glassine | 0,170 |

| Perlite | 0,050 |

| Perlite-cement slabs | 0,080 |

| Sand 0% moisture | 0,330 |

| Sand 10% moisture | 0,970 |

| Sand 20% humidity | 1,330 |

| Burnt sandstone | 1,500 |

| Facing tiles | 1,050 |

| Thermal insulation tile PMTB-2 | 0,036 |

| Polystyrene | 0,082 |

| Foam rubber | 0,040 |

| Portland cement mortar | 0,470 |

| Cork board | 0,043 |

| Cork sheets are lightweight | 0,035 |

| Cork sheets are heavy | 0,050 |

| Rubber | 0,150 |

| Ruberoid | 0,170 |

| Slate | 2,100 |

| Snow | 1,500 |

| Scots pine, spruce, fir (450…550 kg/cub.m, 15% humidity) | 0,150 |

| Resinous pine (600…750 kg/cub.m, 15% humidity) | 0,230 |

| Steel | 52,0 |

| Glass | 1,150 |

| Glass wool | 0,050 |

| Fiberglass | 0,036 |

| Fiberglass | 0,300 |

| Wood shavings - stuffing | 0,120 |

| Teflon | 0,250 |

| Paper roofing felt | 0,230 |

| Cement boards | 1,920 |

| Cement-sand mortar | 1,200 |

| Cast iron | 56,0 |

| Granulated slag | 0,150 |

| Boiler slag | 0,290 |

| Cinder concrete | 0,600 |

| Dry plaster | 0,210 |

| Cement plaster | 0,900 |

| Ebonite | 0,160 |

Source: https://www.econel.ru/teploprovodnost/

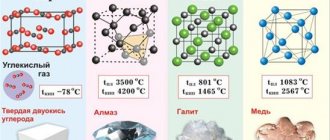

Carbon crystal lattice:

| 500 | Crystal cell | |

| 511 | Crystal grid #1 | α-graphite |

| 512 | Lattice structure | Hexagonal |

| 513 | Lattice parameters | a = 2.46 Å, c = 6.71 Å |

| 514 | c/a ratio | 2,73 |

| 515 | Debye temperature | |

| 516 | Name of space symmetry group | P63/mmc |

| 517 | Symmetry space group number | 194 |

| 521 | Crystal grid #2 | Diamond |

| 522 | Lattice structure | Cubic diamond |

| 523 | Lattice parameters | a = 3.567 Å |

| 524 | c/a ratio | |

| 525 | Debye temperature | 1860K |

| 526 | Name of space symmetry group | Fd_3m |

| 527 | Symmetry space group number | 225 |

Note:

201* The range of atomic mass values is indicated due to the varying abundance of isotopes of a given element in nature.

206* According to [1], the covalent radius of carbon is 77 pm for sp3, 73 pm for sp2, 69 pm for sp, and 77 pm according to [3].

401* The density of graphite according to [3] is 2.25 g/cm3 (at 0 °C and other standard conditions, the state of the substance is a solid).

410* The molar heat capacity of graphite according to [3] is 8.54 J/(K mol).

Story

Carbon in the form of charcoal was used in ancient times to smelt metals.

Allotropic modifications of carbon—diamond and graphite—have long been known. At the turn of the XVII-XVIII centuries. The phlogiston theory arose, put forward by Johann Becher and Georg Stahl. This theory recognized the presence in each combustible body of a special elementary substance - a weightless fluid - phlogiston, which evaporates during the combustion process. Since when a large amount of coal is burned, only a little ash remains, phlogistics believed that coal was almost pure phlogiston. This is what explained, in particular, the “phlogisticating” effect of coal—its ability to restore metals from “limes” and ores. The later phlogistics, Reaumur, Bergman and others, had already begun to understand that coal was an elemental substance. However, “clean coal” was first recognized as such by Antoine Lavoisier, who studied the process of combustion of coal and other substances in air and oxygen. In the book “Method of Chemical Nomenclature” (1787) by Guiton de Morveau, Lavoisier, Berthollet and Fourcroix, the name “carbon” (carbone) appeared instead of the French “pure coal” (charbone pur). Under the same name, carbon appears in the “Table of Simple Bodies” in Lavoisier’s “Elementary Textbook of Chemistry.”

In 1791, the English chemist Tennant was the first to obtain free carbon; he passed phosphorus vapor over calcined chalk, resulting in the formation of calcium phosphate and carbon. It has been known for a long time that diamond burns without leaving a residue when heated strongly. Back in 1751, the German Emperor Franz I agreed to provide diamond and ruby for combustion experiments, after which these experiments even became fashionable. It turned out that only diamond burns, and ruby (aluminum oxide with an admixture of chromium) can withstand prolonged heating at the focus of the ignition lens without damage. Lavoisier conducted a new experiment on burning diamond using a large incendiary machine and came to the conclusion that diamond is crystalline carbon. The second allotrope of carbon - graphite - in the alchemical period was considered a modified lead luster and was called plumbago; It was only in 1740 that Pott discovered the absence of any lead impurity in graphite. Scheele studied graphite (1779) and, being a phlogistician, considered it a special kind of sulfur body, a special mineral coal containing bound “aerial acid” (CO2) and a large amount of phlogiston.

Twenty years later, Guiton de Morveau turned the diamond into graphite and then into carbonic acid by careful heating.

origin of name

In the 17th-19th centuries, the term “carbon solution” was sometimes used in Russian chemical and specialized literature (Schlatter, 1763; Scherer, 1807; Severgin, 1815); Since 1824, Solovyov introduced the name “carbon”. Carbon compounds have the carbo(n)

- from lat.

carbō (gen. carbōnis

) “coal”.