The history of Damascus steel

Damascus steel knives have been used for hunting since ancient times. Such products were used for skinning killed animals and for cutting game. Damascus weapons were considered elite and valued for the following qualities:

- patterns and beauty of the material;

- good strength and flexibility of the blade;

- durability;

- excellent cutting qualities.

Even during the campaigns of Alexander the Great in India, the first mentions of such steel appeared. In battles, he faced the enemy army of the local king Porus. He was wearing a shell made of an alloy, on which Greek swords did not leave a scratch.

The swords of Indian warriors were also made of Damascus. During the Crusades, European warriors were amazed by the sharpness of Arab sabers. Their weapons were made of Damascus steel. The crusaders took trophies home. There are three theories about the origin of steel:

City

According to one version, steel began to be produced in the city of Damascus. But it was not a weapons center; trade flourished there. And there is an assumption that weapons made from this alloy were sold in this city.

Water

Translated from Arabic, Damascus means water. There is documentary evidence that this word was used to describe blades whose surface had a pattern in the form of a rippling surface of water.

Knife Master

There is a version according to which there was a master of Damascus. It is believed that this material was named after him.

But in reality, steel manufacturing technology has spread throughout the world. Nowadays this steel has many names. There is an opinion that Damascus was invented as a cheap analogue of damask steel. It is worth noting that the secret of damask steel was lost.

Damascus steel swords.

About Damascus without embellishment

V.V. Kuznetsov . www.kuznec.com.

Damascus is a welding steel, the recipe of which was lost for centuries and restored at the end of the 20th century, it is a steel with excellent decorative and working qualities, especially cutting - due to the microsaw created by alternating hard and soft layers on the blade.

In one sentence I have contained everything that has been said about Damascus for the last 25 years. This statement pleases the ears of any Damascus manufacturer, but it is only half true, and the other half is a lie and a lie to the ears of the consumer. The truth is that this is welding and decorative steel, everyone can see it and there is no need to prove it. It’s a lie – that the secret was lost and that Damascus cuts better than steel. First, about the lost secret. Encyclopedia, 1903, volume “Technology of Metals”, pp. 116, 117. First quote : “Stainless steel suffers from a lack of uniformity and fine grain, which properties it can obtain during refining. To obtain refined steel, pieces of steel 8mm thick and 80mm wide are prepared by welding, put 20 pieces in a bag, heated to welding heat and forged. Then the strip is bent in half and welded again so that it already consists of 40 layers. Then they heat and forge again, bend it in half again, etc., until they finally get a strip of fairly uniform composition - the carbon tends to be distributed evenly in the hot strip. This is welded refined steel.” (

,

) - products of the 19th century. Welded refined steel. I. Taganov beautifully describes it : “pale gray stripes on the chest of a hawk.” Excerpt from the article “ Khorolug - the combat steel of the ancient Slavs ” magazine “ Kalashnikov ”, No. 4, 2002. Quote two : “Damascus steel is a special type of refined steel. It differs in that it consists of alternating layers of harder and softer steel. Usually up to 320 layers are welded together, that is, the above-described strip of 20 layers is bent 4 times.” This means that 100 years ago the secret was not yet lost. Moreover, two processes were clearly distinguished: refining and damascus. Let us repeat once again: refining is an equalization in composition and structure; steels taken are slightly different from each other; the number of layers is not limited. Later it was established that 30 thousand ÷ 50 thousand. layers is the limit beyond which the unevenness of welded steel is no longer different from cast steel. In Damascus, the steels are different, and the number of layers is limited: 320. Basically, the limitation is not on the layers, but on the welds - only 4, since each heating to the welding temperature leads to a redistribution of carbon and instead of Damascus, refined steel is obtained. Let's take another step towards the truth. We take the textbook “Metal Science”, 1936, Leningrad, p. 125. Quote: “Welding metal is obtained from strips of iron, forming packets, heated to welding heat and rolled in crimping rolls. The resulting metal adds to the disadvantages of cast metal (dissolved oxygen) the disadvantages of welding - the presence of a large number of slag inclusions - and therefore the result is a metal of low mechanical qualities.” The tone is not entirely optimistic; it turns out that welding steel is not that good. I won’t bore you with quotes and will briefly retell everything that is said in this textbook about methods for producing steel. Until 1855 There were such methods: crucible process, puddling steel, cemented steel and welding. Crucible steel is still unsurpassed in quality, but it has ceased to be welded due to the complexity of the process. Firstly, the entire production depends on the quality of the crucibles, secondly, it is difficult to make a large casting, and thirdly, the composition of the steel is difficult to regulate. Pudling steel is only slightly inferior in quality to crucible steel. There is no oxygen in it and its mechanical properties are still better than electric steel. Due to its long fiber, it is the most resistant to tearing and breaking. But it also disappeared, since it is impossible to mechanize the process and control the composition. Cemented steel was of very low quality and was used only after refining by welding. It is from it that not particularly important rods and fastenings in houses, dams, and mines are made. Now some blacksmiths, having encountered such a welded package, think that it is an ancient Damascus. Welding steel improved the properties of crucible steel and utilized crucible and puddling steel, but the result was already worse due to the addition of seams and slag. In 1855 The Bessemer method of producing steel appeared in 1865. – open-hearth, in 1878 – electric steel (first experiments, and in 1900 – industrial production). The old ways of obtaining steel began to die out, starting with the worst. That is, cemented steel immediately disappeared, then the production of the rest began to decline, and in 1928. Old methods produced only 0.8% of global steel production. I have listed the disadvantages of crucible and puddling steel. The textbook clearly speaks about the lack of welding steel, I will repeat it again: welding steel is always worse than the steels from which it is welded. This means that welding steel disappeared due to its low qualities. This is about the lost secret. Now, purely for commercial purposes, it is described in detail that a structure similar to a cable is created, carburization occurs with cast iron powder, and a wonderful microsaw appears. If we compare the resulting structure with a cable, then with one in which half of the threads have been cut. Any layer that comes to the surface at an angle is a potential crack. In the old days, when welding Damascus, they tried to make all the layers parallel, resulting in a poor pattern but greater strength. Due to incorrect welding technology, carbon burns out (more on this later). A microsaw, but it is not micro, but rather resembles a saw for felling wood. In any case, one of the steels that makes up Damascus cuts better than all of that Damascus. The curious can search online and find lab testing results for Damascus. V.I. Basov gave his Damascus to the laboratory of the Chelyabinsk Metallurgical Plant, V.I. Basov and V. Koptev gave samples of their Damascus for research to the Samara State Technical University. The conclusion reads: “The sample failed outside the neck…..there is noticeable delamination…..non-metallic inclusions are visible….poor quality of welding.” In general, this does not disagree with the textbook's statement about weldable steel. I would like to supplement these studies, since nothing is said about the composition of Damascus and its cutting properties. I spent four years on this research (see site) and I can sum it up. The carbon content in damasks of the most famous, eminent masters falls within the range of 0.45% ÷ 0.61%. The cutting properties of all Damascus steel are inferior to those made from 65G steel. (I don’t even mention ShKh-15 steel; it is a hundred times superior to Damascus). The best Damascus is made in the factory. Since ground surfaces are welded in a vacuum, there are no slag inclusions; Damascus is equal in strength and cutting properties to one of the steels included in the composition. And the last step. Take the textbook “Blacksmithing”. We need one phrase: “Steel can be welded together repeatedly with a difference in carbon of no more than 0.5%.” This is a very important, key point; not only do you remember it, but you need to put it down. Each pair of steels can differ in carbon content by no more than 0.5% and will have its own welding temperature. For example, a file can be welded with U-15A, temperature 870°÷900°; 65 G + ШХ-15, t°= 950°; steel 3+ 65G, t°= 1200°. If the difference between steels in carbon is more than 0.5%, they can only be welded once. High-carbon steel is heated to 800°÷850°, low-carbon steel is heated separately to 1200°-1300° and welded, there can be no more welding: at low temperatures low-carbon steel is not welded, and at high temperatures high-carbon steel is destroyed. You cannot weld 3.65 G steel and ShKh-15 in one package. You cannot weld even 65 G and a file (repeatedly). After the second welding, look at the cut: the file has crumbled and this is not restored by subsequent welding. With the same success, you can put damask steel with approximately 2.5% carbon inside and weld the package at 1200°. In fact, they weld. Everything else is wrapped in steel 3, like in an envelope, heated to 1250° and all over the place! Under the hammer. The high-carbon steel inside turns to dust, the edge crumbles, and the knife cuts with a wheeze. They listen to this crunch and say with a smart look: “Yes, the microsaw is a bit large!” A couple of years ago I published an article on the website “On welding high-carbon steels”, judging by the reaction, no one understood anything, so I’m explaining it in a second round, if they don’t understand now, then it’s not my fault. So, we have three pillars on which we can rely: steel refining, Damascus 320 layers (in my opinion, the number of layers is too high), the difference in carbon should not exceed 0.5%. Based on this, we can predict the properties of any Damascus even before it is welded. If you take any steel and connect them together, the resulting metal will not have the sum of their qualities, but their arithmetic mean value, but it will be even worse due to seams and slag. Since dozens of patterns can be obtained from one already welded bag, this does not affect the cutting properties in any way, only the strength. The strongest bag will be without a pattern; the more layers come to the surface, the weaker the product will be. Cutting properties are determined in steel by a high carbon content and proper heat treatment , but not by layers of burnt carbon, saturated with oxygen and slag. Therefore, there should be no Damascus on the cutting edge at all, no low-carbon steel, no alternation of soft and hard layers - this does nothing except deteriorate the cutting properties. For those who think logically, here is the proof. Damascus is welded: 50% 65G and 50% ШХ15 . A knife made of 65G cut a Manila cable 7 times, and a knife made of ShKh15 - 9 times. First, we welded these steels end-to-end, it turned out that half the blade was made of one steel, and half of the other, in terms of cutting properties there would be something in between: the knife would make 8 cuts. But there was an added minus: a seam with slag, like a crack on the edge, which clings but does not cut. Now let's chop this blade into pieces, weld it again, so that on the edge there are 4 pieces ShKh15 and 4 pieces 65G . Cutting became worse, as there were more seams. We make 15 pieces of each steel - the cut is even worse. Question for filling : if the cut becomes worse due to the increase in seams and layers, then when will the moment come when all the minuses will multiply and give a plus! Answer : never. And we have not yet taken into account the combustion of carbon and its diffusion. The microsaw exists and operates, but in damask steel and steel, since the size of its teeth is about 5 microns. Such a tooth can be obtained in Damascus with 3,000÷10,000 layers, although this is no longer Damascus, but refined steel, average from those taken initially. It’s clear that if we take 65G and 55S2G, then with 10,000 layers we have 60GS, with all its properties, but a little worse due to the layers and slag, for which then all the work was done... Is there a Damascus that has an increase in quality ÷ Yes, there are even two types. The first type, which I called “Caucasian” for myself, because “ Gurda ” sabers were made in this way. Two secrets: the first is a small number of layers (60-200) and their strict parallelism, followed by forging the blade to the thickness of a razor. The second secret: carburize only the cutting edge, not the entire surface. Carburization was carried out with a mixture of scale and charcoal, which gives an incomparably more elastic seam than when using cast iron. What did all this result in? A very elastic low-carbon blade, with an edge having a steel strip of 1% -1.2% C. Such a saber cut very well and broke in a vice only after several bends. Increasing the layers and welds cannot add anything, but it sharply worsens the strength. Iron disappears, turning into steel, the number of seams and slag in them increases, carbon on the edge is not added - there is a saturation limit, problems arise with accurately determining the welding temperature, because as carbon increases, it must be lowered, this requires a lot of experience. So 60-200 layers, i.e. the same 4 – 6 welds are the golden mean. The design of the Polovtsian sabers, made from mounds, is similar, but simpler. Always 5 – 7 layers, one welding. The iron is raw, but it was powdered with phosphorus oxides, the content of which on the edge reaches 1.2%. The saber in a vice breaks after 4 - 5 bends, but cuts well.

Polovtsian saber. “Gurda” is structurally the same, only there are more layers.

This is the first method of Damascus, whose properties are the sum of its constituent elements. You can repeat it with steel 45, reinforcing bar and even 65 G , but strictly observing all the conditions: parallelism of layers, a small number of welds, carburization of 1/3 of the strip width with simultaneous thinning of this third. The best scale is sawdust from emery, which must be washed (tormented) and graphite added. The second type of Damascus with a plus is high-carbon steel on the edge and medium-carbon, elastic steel on the butt. This design, despite its simplicity, gives excellent results, which is why many companies have now begun producing three-layer knives. If the linings are made of stainless steel, then another positive quality is added. The overall result depends on what steel is taken and the quality of the entire work. You should always remember rule No. 3: one-time welding of steels with a large difference in carbon. There are few complex structures: a Roman sword (high-carbon steel and a spring are welded together, the spring and raw iron are welded separately, then all together).

Sword "Gladius"

Amuzgin dagger (high carbon steel + spring + decorative damascus ).

Amuzgin dagger. Cutting edge dimensions: 0.5-1mm, width 7-8mm.English knight's sword (refined high-carbon steel inside + decorative damascus on the edges).

Expensive knight's sword.

Japanese sword (high carbon refined steel outside + elastic medium carbon steel core inside).

Tati, katana, etc.

Damascus iron medium carbon high carbon

Those who still remember the beginning of the article will not argue that Japanese and English swords are only two-component. The most revealing one is the Japanese sword. For the high-carbon half, pieces of steel with carbon 1.7% ÷ 1.9% are immediately selected, 15-18 welds in a reducing flame, and even wrapped in paper so that there is no oxygen saturation, 30,000 ÷ 60,000 layers, which is with a thickness of 10 mm . gives a layer less than a micron (and the grain size is usually 5-15µ). That is, the layers have nothing to do with it, the resulting steel has a fine grain and is even in composition. By the way, it is on the polished surface that the pattern of layers is visible, and if you etch, then everything merges into an even gray color, since there is no difference in carbon. The first three designs are more resistant to fracture; there are examples with broken blades, but they are held in place by soft coverings, so they perform their functional functions. Japanese swords still break, despite zone hardening and a soft core, the ratio of hard to soft is too high, about 3:1, it would be more correct the other way around, but we won’t correct the Japanese, let them do as they are used to. Where only steel was taken, i.e. the first two designs, the freedom of creativity is sharply limited, since the choice of steels for the blade is small. Under the same conditions, 65G gives about 70 cuts, ShKh-15 - 70÷90 cuts; Р6М5 — 70÷110 cuts. All the other steels are not even close. Designs with refined steel give complete freedom to creativity, since you can make really high-carbon steel with a good structure. It is clear that everything depends on the quality of welding. After all, not everyone can even weld a file with itself on the fly, but here you initially need to take the U15A ; U16A and no lower, otherwise by the time you get to 1.7% the steel will burn by half. Summarize. Only two types of Damascus have good working qualities. First: raw iron with a small number of layers and welds, with carburization along the edge. Second: welded from several steels, but not mixed, but strictly according to the rules - high-carbon steel on the blade, elastic on the spine. Modern Damascus with mixed layers on the blade is always worse than one of the steels included in its composition. Reasons: carbon burnout, saturation with slag and oxygen, metal destruction due to improper welding. Neither the layers nor the alternation of soft and hard on the blade achieve anything - this is the dilution of good steel with bad steel and slag. There are attempts to make a high-carbon blade and an elastic spine. But since there is great confidence that it is the layers that are being cut, they take U-12 + ShKh-15 , make 1,000÷3,000 layers and consider that everything is in order. No one makes any measurements or comparisons. Since welding is carried out in an oxidizing flame, at an elevated temperature, and there are also many welds to obtain these thousands of layers, then 0.5% ÷ 0.6% carbon remains, plus slag, plus oxygen - that’s the whole result. Carbon must be measured on a spectrograph, not calculated on paper. Any steel can be welded with carbon buildup or burnout; This is where the skill lies, so that during welding the carbon content increases and the metal does not become embrittled, i.e. didn't get oxygen. I haven't written anything new. The same can be read from our theorists. For example, A. Maryanko writes that “ Damascus may turn out no worse than any component of the package, but you should not expect super properties. The main value of Damascus is its beauty” ( Prorez , No. 1, 2000, p. 49). V. Khorev in his book “Weapons from Damascus and Damascus Steel” says that the purpose of Damascus is decoration. What is now accepted as a work product was used for the lining of a dagger or sword in the 19th century. A. Bazhenov, who devoted his entire life to the study of the Japanese sword, does not deify it at all, believing that it is simply a cultural phenomenon that does not have any magical qualities. On average, a sword was made in 3-5 days, some blacksmiths forged 1670 swords in their lives, the hardness of a Japanese sword lies in the range of 56-60. HRC, there are a lot of broken samples. Structurally, the knight's sword is higher than the Japanese one. Damascus coverings act as a clay coating, so hardening is easier and more stable. If everything is welded perfectly and annealed, then you can harden it to the maximum and not think twice about it, even if the core breaks in battle, the entire product will remain working, and the Japanese sword will shatter in half and to smithereens under the same conditions. If one blacksmith makes two swords from the same materials - a Japanese sword and a knight's sword, then with the same cutting properties, the knight's sword will be more resistant to breakage. I write articles based on my experience with the involvement of fundamental sciences - metal science and blacksmithing. I am writing not for consumers, but for young blacksmiths who consider it indecent to read anything on the topic, so they reinvent wheels every day. The happiness from welding damascus from a cable is immeasurable, so it is difficult to land, saying that an elastic patterned steel has been obtained, but it contains approximately 0.3% 0.4% carbon and only oil cuts this damascus. If you don’t have a quantummeter or spectrograph at hand, then you need to have a piece of manila cable - it will immediately tell you what quality the damascus is obtained. If you save time on measurements and comparisons, then there will be no progress; you will never know what happened and how to improve. The first step in obtaining not patterned steel, but Damascus, which has high performance properties, is welding refined high-carbon steel, at least 1.7% C, since U16A still exists and can be found, everything else is worse than it, and you need to do better , rise higher. The step is very difficult, but once you climb it, everything else is easier to do - even welding a katana, no worse than in the Land of the Rising Sun.

For those who sincerely believe in the microsaw on the Republic of Damascus, I present simple arithmetic calculations. The brightest and most attractive damask has 300-500 layers. In order to open all layers on slopes, the blade is not tightened during forging, i.e. it's just a plate, 4-5 mm thick. 5 mm. = 5,000 microns. and if 5,000: 500, then the thickness of one layer is 10 microns, while the rounding of the RK = 2-5 microns, so on the edge there will be sections of the same metal mm long, and the situation described just above is created , i.e. alternating sections of good and bad metals of sufficiently long length. This does not lead to an increase in cutting properties, but on the contrary, it worsens it. Twisting (torsing) the package will not help either, because it is twisted at a thickness of 25-30 mm, and at this time the layer thickness will be 50-60 microns. And further settlement does not occur, this thickness remains unchanged. In torsioned damascus, the layers are located at an angle to the RK and again the result is an alternation of sections of different metals 70-100 microns long, which is not a microsaw. If the number of welds was more than 4, then carbon diffusion occurred and its arithmetic mean value was obtained throughout the entire volume. Metals differ only in color due to different ligatures, but nothing more. So, there are only two types of Damascus: one is the arithmetic average of the components of the package, the second type is the sum. It is very easy to distinguish them; no skill is required. In the first case, all components come into contact with the rotor, which sharply worsens the strength and cutting properties of the blade. In the second - on the RC there is a monosteel, or a multilayer of monosteel with carburized seams, plus linings, internal inserts, or simply a butt made of elastic steel. So, real Damascus, which represents the sum of all the properties of its constituent components, consists of only two parts: a high-carbon RC and a medium-carbon elastic butt. The number of designs of this Damascus is limited: Roman sword, English sword, modern. kitchen 3 puffs and a Kama dagger - one option; Polovtsian saber, "Gurda" and Japanese swords - the second. The difference between these two types of real Damascus is fundamental. In the first case, well-cutting steel is taken and the blacksmith, without interfering with its structure, makes it stronger and more decorative. The second design provides more opportunity for creativity, since the master himself creates the structure of the cutting metal. The proverb says: “Taste is silent, but bad taste screams.” In strict accordance with this rule, a decorative metal with a brightness of color equal to the feathers of a peacock does not possess any properties. Since the layers in it go across the blade, the strength is equal to plywood sawn across. On the edge there are alternating long sections of bad and good metals with burnt carbon and layers of slag. Today there is real Damascus (the sum of its components) - these are products from Damasteel, Sweden; Japanese three-layer kitchen knives and products by master K. Dolmatov (who has been making multi-layer linings for monosteel for a long time). No one makes Damascus of the second type - it is difficult, troublesome and results are not easy to achieve; to achieve the goal you will have to discover all the secrets of the Japanese sword yourself, alone. Because all books talk about the external, but do not reveal the essence.

Composition of Damascus steel

Each blacksmith chooses the composition of Damascus steel experimentally. The most optimal option for steels included in Damascus is considered to be: U8A, ShKh15 and KhVG. U8A steel contains a lot of carbon (0.75-0.85%). It is responsible for the hardness of steel.

There are also alloying elements in the form of nickel, chromium and manganese. Due to its hardness, U8A steel is used in the production of industrial knives. It is used to produce metal-cutting tools, working elements of dies, files and chisels.

ShKh15 steel is used for the production of bearings. Its composition includes carbon 1.05%, chromium 1.5%, as well as silicon and manganese in small quantities. KhGV steel is widely used for the manufacture of measuring instruments.

In addition to carbon, it contains about 09-1.2% chromium. It also contains manganese, molybdenum and tungsten. The interweaving of alloys during the production of Damascus steel gives beautiful patterns, high hardness and strength to knives.

Damascus steel

- This can be illustrated like this. An assembled block of eight layers of metal with varying levels of carbon content in them is forged together. Once the forge welding is complete, the block is bent. If the welding is done with proper quality, cracking and delamination does not occur between the layers - the entire package behaves like a solid steel beam. Having sanded its end and etched it with a solution of ferric chloride, you can see the simplest pattern - parallel stripes. After this, the package is unforged and cut into two or more parts, reassembled and welded. The total number of layers in the finished package depends on the number of layers in the original and the number of folds and welds.

The renaissance in the manufacture of Damascus that emerged at the end of the 20th century gave rise to a huge amount of speculation in this field. Strange as it may sound, truly high-quality working damask, unlike decorative damask, is produced only in very few cases. The main reason for this seems to be the lack of awareness and commercial promotion of this trend: demand gives rise to speculation, and more and more products from a material that can be attributed to Damascus only by appearance are appearing on the market. The lack of information has led to a number of misconceptions that dominate the mass consciousness regarding such material.

The main characteristic of Damascus steel, which determines its advantages, is usually the alternation of layers with a high carbon content, which gives the blade sharpness, and a low one, which gives it strength. In fact, during forge welding of layers of steel with different carbon contents, carbon diffusion occurs (i.e., movement from areas of high content to areas of low). This worsens the cutting properties of the high-carbon components of the package due to the combination of carbon, and due to the abundance of welding seams, the strength properties of the entire blade may even deteriorate. In addition, carbon burnout during repeated forge welding can reduce its content by 0.3-0.4%. In order to compensate for such significant losses, many craftsmen use more severe hardening modes, which affects the strength properties of the RC.

Another popular misconception is that for the package, ancient craftsmen used very expensive and secret grades of steel, which formed patterns of rare beauty. But blades from the 19th century from Germany and France are known, on which even letters and numbers embedded in the pattern can be easily counted. For modern craftsmen who master forge welding technology, creating such patterns also does not present any particular difficulties. The beauty of Damascus steels is based on the difference in the colors of layers of steels with different chemical compositions. For bright lines, plain carbon steels or even low carbon steels can be used.

Light lines.

- 6 (domestic analogue - 5ХНМ) - steel with a high nickel content. When combined with carbon steels it produces brilliant bright lines. This steel is known for its high strength, and its addition to the package improves its strength properties.

— O1 (domestic analogue – HVG) is a popular tool steel with a sufficient amount of chromium to form bright lines in a package with low-carbon and high-carbon steels. It is sensitive to overheating - it begins to crumble, but it welds perfectly at low temperatures.

- nickel - often used for the bright and shiny component of the package. Not recommended for blade material. Nickel is a carbon blocker, and if in a multi-layer package, layers of nickel are exposed to the blade, it will negatively affect the functionality of the blade. Popular for a knife that is less critical to the load of the device, where it forms clear contrasting lines.

Dark lines.

The dark lines of Damascus steel are formed by low alloy carbon steels. By selecting steels with different carbon contents, shades from light gray to deep black can be obtained; light colors are usually formed by low-carbon rolled products. The addition of low-carbon elements to the composition of the package leads to the depletion of the finished blade in carbon, which must be kept in mind when designing and assembling the package. At the final stage of package forging, the average carbon content for most craftsmen varies from 0.6 to 0.8%, and therefore, before assembling it, it is necessary to recalculate the relative amount of carbon for each individual weight component of the package. In addition, the burnout of part of the carbon during forge welding should be taken into account.

When choosing Damascus, you should pay attention to the etching and final coloring of the polished blade. When zone hardening of an unpatterned steel blade is carried out, color variations between the hardened and unhardened parts are also obtained. Using chemical or thermal oxidation technologies, a Damascus blade can be given an additional effect.

The most common carbon steels for Damascus.

- 1095 is a good knife steel that has an excess initial carbon composition and combines perfectly with 15N20 or L-6;

- 1086 (domestic analogue - 85) - lower carbon content, boils well;

- 5160 (domestic analogue - 50HGA) - many craftsmen truly love this steel. This oil-hardened steel has excellent “foolproof” potential - it tends to forgive mistakes with forging and hardening;

- 52100 (the domestic analogue is ShKh15, but it should be borne in mind that this grade often has an excess chromium content - more than 1.5%, which seriously complicates weldability) - this is alloy steel. It is not for beginners, it requires precise control of the heat treatment process, but, ultimately, these difficulties are justified by the quality of the blade;

— W-2 (U9) is a very popular steel: it is well forged and hardened. Has good grain structure.

The main thing when combining different steels is their ductility and welding temperatures. If one of the components of the package begins to flow at welding temperature, while the other still remains hard, the weld seam begins to distort when the package is subsequently drawn out. A large number of stainless steels have this disadvantage.

Pros and cons of Damascus steel

The main use of Damascus steel is in knives. But like any steel, it has its advantages and disadvantages:

pros

- aggressive cutting of Damascus steel knives. It is obtained thanks to the microsaw, which is formed on the cutting edge due to the welds;

- depending on the steels included in the package, the hardness of the material can vary from 60 to 64 HRC. Which has a very positive effect on the duration of knife sharpening;

- One undoubted advantage of Damascus steel is its relatively low cost. There are varieties that are more expensive, but basically the products are budget options;

- Of course, you should pay attention to the beauty of Damascus knives. The unique designs obtained during forged welding cannot be seen anywhere else;

- If a knife loses its unique design, it can be restored. To do this you will need fine sandpaper and acetic acid.

Minuses

- Damascus knives require constant care. They resist corrosion very poorly. After working with the product, it must be rinsed with water and wiped dry;

- the complex process of manufacturing welded damascus, which sometimes greatly affects the cost of products;

- Before putting the blade away for storage, it should be treated with machine oil.

This is what Damascus looks like on knives.

Damask steel and damask: let's understand the terminology

There is nothing fundamentally new in this short note that would not be well known to those interested in this issue. But my personal experience shows that the overwhelming majority of people who have not yet plunged into this exciting world have little idea what they are talking about when the conversation turns to damascus or damask steel. This page is intended for them. For clarity, I tried to illustrate it with examples.

Naturally, the information presented here is not only brief, but simply, as they say, “in a nutshell.” I only hope that it will help to better understand the descriptions of the knives given on the site, and will serve as a starting point for studying really serious articles, links to which are given at the bottom of the page.

Bulat or Damascus?

In principle, any patterned blade (of course, we are not talking about a pattern applied to homogeneous steel) can be called both damask and damask. And it won't be a big mistake. Previously, these concepts were not strictly distinguished. Any pattern was called Damascus, and any blade made of inhomogeneous steel was called damask. Historically, outstanding qualities were attributed to damask blades, but this is rather a semantic load of the term that does not characterize the appearance or technology of obtaining the product. Therefore, we will not consider it now. According to production technology, damask steel has long been divided into “cast” and “welded” or “welded”. Based on this, when describing a specific product, it is more correct to say “ cast damask steel ” or “cooked damask steel ”, then there will be no confusion in concepts.

Cast damask steel

Cast damask steel is produced by melting the initial components in a crucible in a forge. As a result of the slow cooling of the ingot, a heterogeneous structure is formed in it, which subsequently gives a pattern on the blade.

This is exactly what the legendary Indian damask steel was like. But what about the production secret that was lost a long time ago? Indeed, even now the exact technology used in ancient India is unknown. It was hidden so carefully that by the 17th and 18th centuries the secret was lost. This is due to a decrease in demand for damask steel caused by the start of production of high-quality and inexpensive bladed weapons from industrial steel, which led first to a reduction in the smelting of damask steel in India, and then to its complete cessation.

Numerous attempts by researchers to uncover the secret of damask steel were unsuccessful. However, at the beginning of the 19th century, the Russian metallurgist Pavel Petrovich Anosov developed a technology with which he was able to obtain steel that matched the pattern and quality of the best varieties of Indian damask steel. It is on the basis of this technology that damask steel is poured now. The main mistake of researchers before Anosov was that they tried to obtain a pattern by adding additives to the chemical composition of the alloy. And only Anosov managed to prove in the course of experiments that damask steel differs from ordinary steel not in its chemical composition, but in its physical structure.

According to more or less established terminology, in Russia today the word “damask steel” is usually understood as cast damask steel. I stick to this option on my site.

| Damask steel of the famous Kara-Khorosan variety on an 18th-century Turkish saber with a Persian blade (see photo at the top of the page). |

Types of damask steel (by chemical composition)

Despite the fact that the basis for understanding the essence of damask steel is its physical structure, it, like any steel, can contain additional elements in its composition in addition to iron and carbon. If damask steel is smelted on the basis of carbon steel with the addition of cast iron, and the composition additionally includes only natural impurities in small quantities, then such damask steel is usually called “carbon”

.

Like all carbon steels, it is susceptible to rust. Modern metallurgy, which has a huge range of alloyed steels, has pushed craftsmen to create “alloyed”

and

“stainless”

damask steel. They are smelted from alloy steels and can be corrosion-resistant.

| Carbon damask steel , blacksmith Pampukh I.Yu. |

| Stainless steel damask steel , blacksmith Arkhangelsky L.B. |

Wootz

In the old days, after smelting, a damask ingot was either forged on site or sold as an ingot, called a “wootz”. Caravans with them went far beyond India. These ingots had the shape of a small loaf of bread. Thus, the word “Wootz” refers specifically to an ancient ingot made in India.

In English, the word " wootz " serves both as a definition of the ingot itself and of damask steel as a whole. Including modern damask steel is also called “wootz”. To designate a damask blade, the phrases “Wootz Blade” or “Wootz Damascus Blade” are used.

| Wutz , 18th century. Maximum dimensions 53*44mm. Weight 1 lb (approx. 450g). (Data from the online auction www.ebay.com). |

Welded damask steel (damascus)

Welded damask steel, as the name suggests, is produced by forge welding. To do this, a package of steels with different carbon contents is assembled, which is welded together, then folded in some way (for example, in half) and forged again. And so the number of times necessary in each specific case. At the same time, the number of layers grows exponentially. So, if the initial package had 8 layers, then after the first welding there are 16 of them, after the second 32, after the seventh 1024, etc.

According to the established terminology today, welded damask steel is more often called damascus. I stick to this option on my site.

The English “damascus” corresponds to the Russian “damascus” in the meaning of “welded damask steel”.

Types of Damascus

Based on the chemical composition, similar to damask steel, Damascus is divided into carbon and stainless steel. Due to the difficulty of welding alloy steels, carbon Damascus is most widely used. All types of Damascus presented below are illustrated specifically with carbon Damascus.

| Stainless steel Damascus is produced on an industrial scale by the company Damasteel (Sweden). In Russia, stainless Damascus is made by blacksmith A. Umerov. |

| In principle, it is possible to weld carbon steel with stainless steel, as on this blade by the blacksmith Matveev, but this is an extremely rare option. |

Types of Damascus

| Blade: A. Bely | “ Wild Damascus ” does not have any structured pattern, which in no way impairs the quality of the blade’s cut. |

| Blade: Fedotov's workshop | " Plain Damascus " has a fairly stable repeating pattern. Although in this case, when forging, the master does not strive to create a specific pattern, it is obtained automatically as a result of using the simplest technology for forging Damascus steel. Therefore, it can be considered a subspecies of the “wild” Damascus. |

| Blade: M. Arkhangelskaya | “ Stamp Damascus ” has a characteristic repeating pattern, the shape of which is determined by the stamp used to create it. The name comes not from "stamping" in the sense of low-quality in-line production, as some people think, but from "stamp" as a blacksmith's tool and technique. |

| Blade: S. Bobkov | “ Mosaic Damascus ” has a pattern that is repeated along its entire length, the complexity of which is determined only by the skill and intention of the author. For such damascus, the package is initially assembled in such a way that after welding the desired pattern is obtained. |

| Blade: A. Bely | “ Twisted mosaic or Turkish damask ” has a characteristic pattern obtained as a result of repeated twisting of the workpiece around its axis during the forging process. |

| Blade: M. Arkhangelskaya | “ End mosaic damascus ” is a subtype of mosaic damascus and is distinguished by the fact that plates are cut from the end of the finished block, which are either welded onto the blade in the form of facings, or form the middle of the blade, to which the blade and butt are welded. |

| Blade: Yu.Sarkisyan | " Fibrous Damascus ". A rather rare species among us. In appearance the blade looks like damask steel. If in other types of damascus the layers during forging are pulled out over the entire length of the click, then fibrous damascus consists of short fibers. When forging, the required number of layers is first collected, as in ordinary Damascus. Then the workpiece is rotated 90 degrees (the layers are arranged vertically), and similarly, by unforging, scoring and folding, the desired number of fibers is collected. According to S. Lunev, the best Japanese swords have a complex fibrous structure. |

| Blade: M. Arkhangelskaya (four-row mosaic damascus) | " Multi-row Damascus ". This rather refers to the blade, and it would be more correct to say “multi-row Damascus blade.” Such a blade is obtained by welding 2 or more strips of Damascus located along the blade. In this case, usually a “working” (most practical) damascus is placed on the cutting edge, and then a more complex artistic one is placed further towards the butt. |

| Illustration taken from an article by L.B. Arkhangelsky | " Powder mosaic damask ." Mainly manufactured abroad. The essence of the method is that first, a cliche is made from a well-weldable metal that contrasts when etched with ordinary steel. It is placed in a container and filled with powdered steel. Under the influence of high temperature and pressure, all this is sintered into a single ingot, which is then unforged at the discretion of the master. In this way, you can create images of almost any complexity on the blade. |

The types of Damascus listed above are the most common. They differ in forging methods, which results in different patterns on the blade. The master can combine different methods and obtain completely unusual and original patterns. Only a high-level specialist will be able to unravel the secrets of another master. And we will just admire this bewitching and alluring pattern on the blade.

| Blade: L. Arkhangelsky | An example of this is this blade, which in appearance is difficult to classify as one of the above types. |

If you are interested in the topic of patterned blades, you can find extensive material on damask steel and damask at the following links:

– section “Articles” of the website of master I. Kulikov;

– section “Articles” of the Arkhangelsk blacksmiths website;

– section “Articles” of the website of master I. Pampukha;

– Evgeny Charikov’s website about historical and modern cast damask steel “Dendritic Steel”;

– French-language website “Passion du damas”, which describes and illustrates with photographs methods for obtaining various types of damask.

Source : bladesmagic.spb.ru

Post Views: 2,634

What is real Damascus

In the old days, the production of such steel was kept secret by every craftsman. The cost of the products was very high. But even today, some types of Damascus steel knives belong to collectible categories.

To obtain true Damascus steel, you must forge a twist of carbon steel rods or plates. Thanks to forging, the layers are flattened and become very thin. This multilayer structure provides the blade with the necessary strength characteristics.

The difference between damask steel and damask

The characteristics of damask steel and Damascus steel divided people into two camps. When purchasing products, people rely more on personal preferences.

By external signs, in a particular case, by pattern, you can clearly distinguish these steels from each other.

The main advantage of damask steel is the ability to make an alloy alloy. This greatly simplifies the maintenance of the knife and prevents the blade from corrosion. But creating Damascus with such characteristics is a very complex process, and it is considered impractical.

Damask steel knives.

Characteristics of Damascus

The hardness and flexibility of the blade are considered the hallmark of Damascus steel. To achieve such characteristics, you have to alternate layers of different steel. High-carbon steel gives sharpness to the product, while low-carbon steel makes the knife durable.

The secret of such steel lies in the correct combination and certain proportions of alloys. Damascus steel is produced by forging from a package of different types of steel. The alloy contains a multilayer structure. It contains few alloying elements, hence the low corrosion resistance.

Forging Damascus in a forge

The production of Damascus can occur in several different ways; we produce the so-called ''welded Damascus''. This technology involves the selection and welding of workpieces (hence the name welding) from various grades of steel, soft and hard, which allows achieving the necessary characteristics for good cutting properties of the blade.

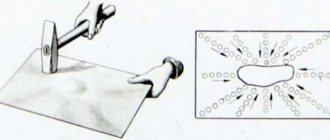

In the photo (from left to right): assembling and welding a package of steels, twisting an unforged package, forging a package of steels with a hammer.

Damascus is not a metal found in nature in its pure form, but consists of a package of steels selected by us as a result of a large number of tests. To create it, we use a package of four steel grades (ShKh-15, KhVG, U8A, steel-3), each of which is necessary to impart the necessary cutting properties to the final product.

Let's move on to the technological process itself in more detail. After the workpiece has been prepared from a package of steels, it must be heated to a bright red color, after which you can proceed directly to forging. The forging process is repeated three times, the thickness of the forged strip in the first two stages does not have clear regulation, and in the third final stage it is made as close as possible to the thickness of the butt of the final product, in order to avoid unnecessary consumption of metal and lengthening the processing process.

Next, the workpiece is given a rectangular shape for the next technological process - twisting. The fragment directly with twisting was not included in the video, but there is nothing particularly complicated here, the hot workpiece is twisted in a spiral, for as many revolutions as can be achieved before the metal hardens - as a result of which the shape of the workpiece changes from rectangular to cylindrical ( You can see the unforging of the twist at the 10th minute of the video). The texture of the pattern on the blade depends on the number of twists.

In addition, I would like to draw your attention to such a moment of the technological process as borax sprinkling (white powder), which is used during forging of the workpiece after twisting to draw out slag and scale, which avoids the appearance of fistulas and lack of penetration. After this, a strip of metal is obtained from which the blades themselves will be made. Now we move on to the workshop, where a knife will be made from the strip, and finally, a few more photos from the forge.

Types of patterns

Before listing the different types of Damascus, it is worth making a short note. In order to produce stainless Damascus, it is necessary to assemble a package of alloy steel with the correct additives. It is welded in a vacuum.

This steel is then forged and the heating cycle is repeated. Modern technologies can handle such a process, despite the complexity of the process. Sometimes you can find kitchen products with patterned stainless steel linings.

Wild Damascus

It got its name because of the disordered pattern. It is quite simple to manufacture and is considered the most common type. A package is made from several types of steel and welded into a single block. It is repeatedly bent and forged.

The layers of metal mix randomly. The surface of the finished product looks uneven. This method goes back hundreds of years. Due to the uniqueness of the pattern, it is highly popular among collectors.

Wild Damascus.

Stamped

This is one of the varieties of traditional damask, with a more uniform pattern. It can alternate geometric shapes: stripes, circles and rings. It is made in two ways:

- the pattern is applied using a metalworking method, using a drill or a router, and only then the package is forged;

- The package is welded, and the stamp is struck in a given order. The finished blade must be polished. This way they achieve a clearer picture.

Stamp patterns can be mesh, wavy, stepped, ringed and rhombic. The patterns look like wood veneer or circles on water. The types of patterns are in turn divided into a wide variety of patterns.

By the corporate style, you can even recognize the hand of the master. In America, damask with a type of pattern - peacock eye - is very popular. The pattern looks like crosses, resulting in an imitation of barbed wire or mesh. To produce such a pattern, uniform drilling of the workpiece is used.

Example of stamped Damascus.

Mosaic

It is classified as a modern type of Damascus. Thanks to the specific manufacturing method, it got its name. The layered structure gives a beautiful decorative effect. The steel is assembled into a package similar in principle to a mosaic.

A subspecies of this type can be called mosaic end damask. This is a blade with welded strips of mosaic damascus cut from the end of the finished block. Such a strip or several strips can be applied in the middle of the blade.

Mosaic Damascus.

Turkish Damascus steel

One of the traditional varieties of patterned steel. A bundle of intertwined steel rods is used for forging. It is clear that the composition of the rods is varied. A complex pattern with many smooth wavy lines appears on the finished product. Their size depends on the chemical composition of the metal and the diameter of the rods.

Examples of Turkish Damascus steel.

Japanese

Laminated steel has a fine structure. The surface of such knives is etched. The structure of the steel is revealed through unusual polishing. Only the blade itself is hardened. The result can be seen in the properties of the Japanese sword. The handle remains elastic, and the blade becomes hard and brittle.

Japanese knives made of Damascus steel.

Shell

A metal pipe or container is used to connect mosaic elements. Various steels are placed inside. Next, the container is filled with inert gas or oil. In the process of heating the workpiece, oxygen is bound.

A neutral environment is obtained inside the shell, and the pipe is completely welded. In this state, the package is heated to welding temperature. After the formation of a single mass of steel, the shell is removed. Next, the workpiece can be forged.

Shell Damascus.

Fiber Damascus

This method is used in the manufacture of high-quality Japanese swords. When the package is properly forged, the steel hairs do not stretch over the entire length of the blade, but, on the contrary, are finely chopped and arranged in layers at right angles. This metal is very similar in structure to damask steel.

Fiber Damascus knives.

Technological

Holes are cut out in the steel bar in accordance with the specified pattern. Rods of another metal with a different chemical composition are inserted into these holes. Inserts and holes are cut with a plasma cutter. The package is then diffusely welded.

The advantage of this method is the ability to create the necessary drawing and various images. The pattern covers the entire thickness of the blade, which distinguishes it from surface engraving or etching.

Examples of technological Damascus knives.

Combined

This method includes the classical and traditional manufacturing method. Hence the name of the method. A stamp pattern is applied to the block assembled using the mosaic method. If a relief is applied by drilling or milling, then the alloy is forged and etched.

In this case, grinding is not used. It is also possible to combine the wild Damascus technique with metal inserts with contrasting properties. Nickel may be another alloy in composition. The white color will stand out against the overall black and gray pattern of the blade.

Combined Damascus knives.

Industrial

This method is used at large production sites of metallurgical enterprises. The quality of such blades is in no way inferior to the handmade work of masters. The scale of the process is, of course, large. Wild, combined and mosaic damask is produced industrially.

Industrial Damascus.

Damascus steel.

Damascus steel - an excursion into history. Forging was a process by which a blacksmith produced steel and iron from an alloy that was produced by mixing ore and coal in a furnace. The upper layer of the alloy was relatively soft; inside, due to the higher concentration of carbon, the alloy was distinguished by its high strength. Over time, improving the technology of forging, metal processing, and blacksmithing, craftsmen learned to produce Damascus steel

.

And now blacksmiths in different countries continue the customs of ancient craftsmen and are constantly trying to improve the properties of the alloy so that it retains its cutting properties, is stronger and more resistant to corrosion, elegant and practical. It was much more difficult for specialists of past centuries to achieve a good result than in our time, when metallurgy gives us a considerable number of different alloys. To obtain a high-quality alloy (Damascus steel),

you need the correct choice of steels to be welded, knowledge of their physical and chemical composition, and the ability to skillfully process the material.

Based on these factors, you need to obtain steel that can be used to make knives and blades. Blades made of Damascus steel are the pinnacle of blacksmithing, an indicator of the highest skill of a blacksmith. Currently, Russian blacksmiths are among the most brilliant craftsmen - continuers of the traditions of the ancient art of forging. Types of Damascus steel and manufacturing methods

In ancient times, there were two types of iron: malleable iron and cast iron containing over 1.5% carbon, which cannot be forged.

Forged iron and cast iron did not meet the requirements for the manufacture of weapons (swords, knives): cast iron soon broke, and wrought iron bent. Hardness and elasticity are what Damascus steel combines flawlessly. Whoever possessed a weapon made of Damascus steel had an undeniable advantage over the enemy. How is Damascus steel obtained?

Several steel plates of different grades are laid sequentially in a layered package.

The size of the steel plates can be different; the plates must be smooth; to prevent the plates from falling apart at the ends, they are welded or wrapped with heat-resistant wire. Often the blacksmith will make one plate longer to use as a handle. I heat the plates to a temperature slightly below the melting point of the metal. Not all experienced masters can do this. If the temperature is too high, the carbon burns and the steel can be thrown away; it cannot be forged. If the temperature is low, the steel will not be welded. You also need to ensure that the plates are heated evenly along the entire length of the product. The required temperature can be seen by the color of the steel. After the steel has acquired a pale yellow color, you can begin forge welding. The work is quite fast; welding of steel occurs in a very limited time and temperature period. Steel should not be left in the open air for a long period of time due to the appearance of an oxide film on its surface. Many specialists use fluxes. The flux begins to melt and falls on the workpiece, thereby preventing the creation of scale. The steel package is immediately placed on the anvil and by striking the workpiece from one edge, fluxes and impurities are “displaced” to the other edge, and the plates are welded. All this is accompanied by abundant sparking. If everything went well, then you get a package of alloy (laminated Damascus steel). If you need a larger number of layers, you need to forge the product, fold it in half and weld it again. Once the required number of layers has been obtained, you can begin to create a drawing, which can be applied in different ways, as indicated below. The patterns appear later, after the steel is forged and the lower layers of metal protrude. Cutting ability, resistance to rust, color tone, change in metal during etching depend on the initial grades of steel used in Damascus steel. The alloy (Damascus steel) is not stainless, due to the lack of chromium in it, it contains at least 13%. Damascus steel is patterned by etching with sulfuric acid or ferric chloride. An aggressive environment affects different steels differently; as a result, after etching, the layering of the steel becomes clear, which is perceived as if it were a pattern. The number of patterns and their combinations in Damascus steel is unlimited. There are three types of Damascus steel: layered, torsion and mosaic. Layered Damascus steel.

This includes whole varieties of Damascus steel, where the layers are located parallel to the blade.

Simple knives have from 40 to 120 layers. Once upon a time they tried to forge steel more gracefully and thinner, thereby trying to improve its cutting properties. However, since extremely thin Damascus steel is difficult to distinguish with the naked eye, and by looking at the product, not everyone will be able to determine that it is Damascus steel. Nowadays, they are trying to limit the number of layers. "Wild" Damascus steel.

Judging by the name, the pattern on this steel has a chaotic, one might say, “wild” configuration. Unlike most other varieties, when making, they do not purposefully try to obtain some kind of conditioned pattern - all patterns are organized spontaneously. In America, a similar species is called Random Damascus. After this finishing, one of the steels included in the composition remains light, which is explained by the higher nickel content, the other darkens. By keeping steel in acid for a long time, something like a relief appears, since the “weaker” layer is removed under the influence of acid. Big and Small rose. This grade of Damascus steel is produced by stamping layered steel. The blacksmith presses a template into the heated metal, as a result of which some layers partially merge and, after grinding, the template pattern appears on the surface of the part. It is important that the stamped pattern is quite deep because it may disappear during subsequent sanding.

Japanese Damascus steel.

This type of layered steel is distinguished by its extremely thin structure, so some layers cannot be seen with the naked eye. In some cases, the number of layers reaches up to 2 million. If you take a steel package with 8 layers, then when laid eight times you can get 2048 layers. Japanese Damascus steel is pickled and its structure is revealed through special polishing. This steel stands out from other types not only by its structure. Its characteristic feature is the hardening line on the blade called Hamon. In order to carry out a real hardening line, the blade is covered with a special clay mixture, except for the blade, so only the clay-free area is subjected to hardening. This type of hardening affects the properties of the sword: the sword remains elastic, only the blade becomes hard, even brittle. Tape Damascus steel. For the manufacture of this type, layered Damascus steel is used, which is stamped measuredly perpendicular to the center line of the blade. The ribbon pattern appears during subsequent finishing. And here the depth of the stamp must be deep so that the design does not disappear after processing.

Nickel Damascus steel.

Nickel plates are added.

Nickel cannot be hardened and this negatively affects the cutting properties of the blade; one advantage of nickel, an alloying element, gives the steel resistance to etching, and makes polished steel lighter. However, if any thin layer of nickel gets into the blade area, it will wear unevenly. Torsion Damascus steel.

Torsion Damascus steel is made from layered steel, having from 8 to 33 layers, is produced in the form of rods and, when hot, is spun into a rope.

Rods twisted clockwise and counterclockwise are welded. The production of this type is labor-intensive; the blacksmith must first produce selected layered steel. When twisting, he must ensure that the rods do not break as he tries to make as many turns as possible. Turkish Damascus Steel

Turkish Damascus steel has six or more strands available in the alloy.

This type of steel is very expensive to manufacture and is therefore considered one of the highest quality and most expensive types of Damascus steel. Torsion steel with cutting bar.

To improve the sharpness of a knife or blade made of torsion steel, a cutting bar made of fine-grained Damascus steel or monosteel is forged onto the blade.

The knife will have a beautiful appearance and be practical. A cutting bar made of finely formed Damascus steel sheets makes the structure more uniform; such a bar requires high-quality steels, but twisting them may cause problems. It is necessary to ensure that the line between the cutting bar and the first twisted strip is smooth. Damascus steel from chainsaws or wire.

The real appearance of Damascus steel causes numerous controversies among many amateurs - adherents of the purity of Damascus steel. For manufacturing, they use saw chains, steel wire harnesses that can be hardened, and weld them into blanks. They use chains from motorcycles, which does not leave bikers indifferent. The appearance of the finished products is quite tempting, but the cutting properties of the blades cannot be called excellent, since these materials are not intended for the manufacture of blades.

Mosaic Damascus steel.

The patterns here are collected based on various types of steel.

The production of this type of Damascus steel is carried out using presses that ensure uniform processing. The patterns consist of profiles (quadrangular) that are adjusted to each other, which allows them to achieve the best welding. After the steel package is welded, 25-30 mm plates with a mosaic pattern are cut from it. The plates are entirely suitable for making cheeks or handle poms. If they want to make a blade from these plates, they are combined together and welded. Damascus steel from meteorite iron.

The components of this exotic species are hardened carbon steel and pieces of meteoric iron.

The layers that stand out on the surface after etching are nothing more than gaskets made of meteoric iron - due to the higher nickel content, they are not affected by acid and preserve the light coloring. STAINLESS DAMASUS STEEL Forged Damascus steel.

Steels with a high chromium content are not so easy to weld; despite this, specialists still have separate techniques.

Chromium, coming into contact with oxygen in a heated state, immediately forms an oxide film that interferes with the welding of steel layers. Specialists who have studied the manufacturing process manage to minimize the flow of oxygen during welding. The alloy obtained using a method that is expensive in its technology is becoming more and more famous. Powder metallurgy makes it possible to combine alloying elements in an alloy in concentrations that are inaccessible to simple casting techniques. In the aviation industry, using this method, so-called superalloys are formed that can withstand significant loads. The starting material is fine metal powder, sprayed through special liquid metal nozzles in a vacuum or passive gas. Individual layers are formed by backfilling, during which a variety of metal powders are used. Powder layers in a dough-like state are sintered together at high pressure and high temperature, then the workpiece is shaped as for “ordinary” Damascus steel. The patterns are stamped, and the rods are rolled up, the subsequent finishing of the blade is carried out without any questions. Thanks to high-quality “impurities,” the sharpness of knives and blades and corrosion resistance are very high. Damascus steel, made by powder metallurgy, has a special property: when tempered at a temperature of 500°C, its hardness increases again. This property of steel is used to give the steel a certain color by heating it. The master heats the blade after hardening to a temperature of 500°C, as a result of which its surface acquires a rather special blue-red hue. The hardness of an ordinary steel blade at a temperature of 500°C would decrease significantly. Unfortunately, such tarnish colors generally do not last very long, and secondary heat treatment of most finished knives is no longer possible. So the coloring of metal obtained by tempering is only suitable for knives displayed in a display case. Fused Damascus steel.

This variety, familiar under the name wootz, is an alloyed steel.

Various steels are united not by forging, but by melting. When heated to the melting point, all kinds of ores and charcoal are added to the steel in the form of impurities. The dagger shown in the picture is called Djambija, it is approximately 200 years old, and its homeland is the Indo-Persian region. The so-called royal wutz was used as a starting material - CAST INGOT

, taken directly from the crucible from which the blade was formed.

With the help of rubies fixed in special clamps, the blade was sanded, then polished to shine with a polish made of resistant Wootz steel and finally treated with plant juices so that the Jauhar - a pattern characteristic of Wootz steel - was clearly visible. What to prefer?

The preference for one or another type of Damascus steel depends on many factors, but the final result is still a matter of taste.

Damascus steel, made by powder metallurgy, impresses with its beautiful sharp blades and great corrosion resistance. Traditional Damascus steel attracts with its sincere beauty, it is easily sharpened, but at the same time it becomes tarnished and susceptible to corrosion. Video from the Union of Kuznetsov, a master class by one of the most famous Russian blacksmiths, the author of scientific and journalistic works on forging metal science, the history of damask steel and damask Leonid Borisovich Arkhangelsky: Stamp Damascus Part 1. Stamp Damascus Part 2. Pattern formation.

Does Damascus rust?

The answer to this question is unequivocal - yes, it rusts. But traces of corrosion can be easily removed with a rag and gun oil. It is not recommended to use abrasives for these purposes. You can scratch a polished blade.

For the rust removal process, hard rubber should be used.

And you will definitely need a special liquid. After using the blade, it must be wiped dry. For storage, it is recommended to lubricate the product with oil or fat and place the knife in a dry place. If you plan to store the knife in a damp place, wipe it with regular Vaseline.

But you can also find stainless steel models of knives made of Damascus steel. This effect is achieved by special steel additives. This ensures corrosion resistance of the product. But stainless steel cannot maintain an edge for a long time, for this reason such knives are not very valued by real Damascus lovers.

Do you have a Damascus steel knife?

Of course! Not yet...

Knives and other edged weapons from Damascus

Using a knife as a cutting tool requires holding it comfortably in your hand. A small crosshair is made on Damascus steel knives, and small stops are made on the handle for the index finger.

Handle material may vary. Preference is given to natural materials. But handles are also made from synthetic raw materials. The advantages of a Damascus knife include the following:

- light weight;

- excellent cutting qualities;

- unique patterns, beautiful appearance;

- durability of the product.

Household and travel knives made of Damascus steel

A very reliable tool for everyday use. They can cut almost any food: fish and poultry, pork, beef, vegetables, fruits and much more. For fillet knives, special knives with a wide blade are used.

Tourist knife models are valued primarily for their high wear resistance.

Damascus blades are perfect for extreme tourism. Knives with a small blade are made for hunters and fishermen. They are great for skinning prey.

Also, small folding products are made for camping. They are ergonomic, safe to move and do not require a sheath. This knife can be put in your pocket and quickly removed if necessary.

Damascus folding knives.

Features of using a knife made of Damascus steel

As it has already turned out, knives made of Damascus steel are widely used in everyday life and in camping conditions. Proper sharpening of products can extend their service life. Follow these guidelines:

- Preparatory procedures are required, in the form of a preliminary inspection of the blade for damage and chips. Sharpening a low-quality cutting edge will lead to subsequent loss of sharpness.

- Before sharpening, it is necessary to study the previous sharpening angle of the product. Smaller angles are preferred and must be observed.

- Be careful during the sharpening process. If you move inaccurately, there is a possibility of bending the soft layer onto the hard one, in the area of the cutting edge. Outwardly, the blade may look sharp, but in reality it will not be so.

- It is not recommended to use automatic attachments during the sharpening process. This procedure must be performed manually and feel layer by layer. To begin with, use a coarse-grain abrasive. Then the transition goes to medium and finally the finest grain is used.

- Movements should be as smooth and uniform as possible. Do not use sharp or jerking movements. The transverse sharpening method is not suitable for Damascus steel. Here you will need to shoot evenly, exclusively along the blade.

- There is no need to press hard on the knife while sharpening. This can lead to deformation of the softer layers of the product. A careful attitude will lead to maximum effect.

- Observe the factory sharpening angle of the product. It is very important during the process. It should be taken into account that soft layers are easily deformed and begin to overlap the harder ones.

- The corrosion resistance of the blade depends on the final processing of the product. At the finishing stage, it is recommended to walk with a napkin soaked in citric acid. You can also treat the product with beeswax.

If you take care of the knife and store it correctly, the Damascus will retain its famous qualities for a long time. The product gained popularity for its aesthetics and exclusivity. Interest in real Damascus steel will never disappear.

Perspective on Damascus Steel Knives

Damascus steel knives are in demand by beginners and professional hunters. The unique appearance of the products attracts collectors. The tools are quite popular due to their beauty, functionality and reliability.

Damascus steel is used to make many products of various types. Folding knives are also very popular. There are no problems with the sale of such knives. But it should be borne in mind that there are many fakes on the market. Be careful when choosing a blade.

Damascus steel knives

Damascus steel is obtained by forging from a package consisting of different types of metal. Thanks to the presence of these layers, a Damascus steel knife has a characteristic pattern on the surface. The main advantage of Damascus is the combination of hardness and flexibility, which is obtained precisely due to the “mixing” of different types of metal.

Hunting knife – Weasel

This is a classic hunting knife made of high quality materials. It is an ideal cutting tool. The knife is equipped with a sheath made of genuine leather with a convenient suspension on the belt. Product characteristics:

- Total length: 225 mm;

- Blade length: 105 mm;

- Butt thickness: 3.7 mm;

- Blade material: Damascus;

- Handle material: wood;

- , Russia;

- Weight: 137 grams.

Knife for hunters.

Knife – Bear

The Bear hunting knife is distinguished by excellent materials and excellent cutting characteristics. The blade is made of Damascus steel and has a recognizable pattern. The handle has finger grooves that provide an ideal grip. Knife characteristics:

- Knife length: 300 mm;

- Blade length: 155 mm;

- Handle length: 145 mm;

- Maximum blade width: 33 mm;

- Butt thickness: 3.0 mm;

- Blade steel grade: Damascus steel;

- Handle material: wenge;

- Sheath material: leather;

- , Russia;

- Weight: 229 grams.

Hunting blade.

Hunting knife – Wolf

Handmade hunting knife from the Russian master Bessonov. The knife is ideal for outdoor trips, where it can easily cope with any hard work. The slightly curved blade is made of real Damascus steel, so it has an aggressive cut and a large margin of safety. Blade characteristics:

- Total length: 272 mm;

- Blade length: 145 mm;

- Butt thickness: 2.1 mm;

- Blade material: Damascus;

- Handle material: wood;

- , Russia;

- Weight: 158 grams.

Product for hunters.

Damascus knife: product features

The surface of the product is also original - it is visually heterogeneous due to the patterns that are formed during manufacturing. There are two types of Damascus steel that are used to create knives:

- welding - obtained by repeated forging of a steel package;

- refined - during smelting, harmful impurities are evaporated from it.

Every housewife dreams of getting a knife made of this metal: it is ideal for the kitchen as a cutting knife. There are also hunting, fishing, and camping knives on sale, which are valued by professionals. Expensive designer handmade products are usually bought as gifts; many of them are made to order, complemented by handles made of precious wood.

You can't buy Damascus knives cheaply. For example, Japanese Yaxell brand knives cost 12,000-22,000 rubles. A folding knife Samura can be purchased for 3000-5000 rubles, a folding knife from the workshop of Sergei Marychev - for 2500-5000.

Yakut knives or simply “Yakuts” (Russia) are very popular. They have a characteristic feature - the asymmetry of the blade. In combination with a birch handle, such products do not sink in water due to their special design. If you buy a knife from the manufacturer, you can find it for 3,000-10,000 rubles.

According to reviews, Kizlyar knives with a straight blade are also good. Their advantage is in the applied grooves, which make the “kizlyar” lighter. For hunting and fishing, they often buy knives with a hook blade, which are very convenient for gutting animal carcasses and large fish. How much does such a thing cost? The price can reach 6,000-30,000 rubles depending on the brand.

Damascus steel products have their pros and cons. They need to be properly cared for: due to the presence of carbon steel in the composition, rust may appear on the surface. The simplest preventive measures will help you avoid such trouble.

Making a knife from Damascus steel

You can make a Damascus knife with your own hands. To do this, you need to familiarize yourself with thematic photos, videos of how such blanks are made, and also select all the necessary devices and consumables.

Materials and tools

To create a knife, you need to prepare the following materials:

- plates made of carbon steel of two grades (the higher the carbon content, the better the blades);

- borax (sold in hardware departments);

- rod for welding a knife blank;

- quick-drying epoxy glue;

- brass rivets;

- ferric chloride;

- vegetable oil for steel hardening;

- wood for the handle.

You will also need a number of tools for the job. First of all, you need an anvil. It is better to equip a real anvil, but a piece of rail or a large metal sledgehammer will do. You also need a heavy hammer (1-1.5 kg in weight) and a forge capable of maintaining a high temperature. Other required equipment:

- welding for welding plates, securing reinforcement (wire can be used);